Cracking the code on cultural transformation

I was 13 when I ate my first rattlesnake.

This rite of passage at the Otero County Fair & Rodeo was one of the many things I found myself trying on as I attempted to grok a new culture; this one unique to rural New Mexico, which was my re-entry point into life in the United States after 12 years abroad. I had arrived 3 months earlier in possession of a British accent, Val Kilmer’s hairstyle from Top Gun, a physique evoking that of a baby giraffe, and zero familiarity with the music of George Strait. Once again a stranger in a strange land.

I had a peripatetic childhood, moving every 2 to 3 years; usually to a new country and into a community and school that was either parochial, with kids who knew each other from birth and whose parents and grandparents had often attended the same school. Or one which was wildly diverse, with a potpourri of nations represented and populated largely by similarly nomadic children of families engaged in military or diplomatic service.

To be a ‘military brat’ is to suffer a particular flavor of psychological disorder. Without question, my nomadic childhood provided lots of material to explore in therapy. And although many challenges come along with such frequent dislocation, it did help cultivate cognitive flexibility, cultural competence, and other aptitudes which are invaluable if your vocation ends up being one predicated on catalyzing organizational transformation.

Each time I was uprooted and repotted, the cycle began again…

Chase after the logic of this place and its people. Ask questions, map similarities, look for what’s familiar to something I’ve seen before, and identify for further study those things that are truly new.

I became conditioned to look at the world as if it had a secret overlay showing all the connections between and among things. Trying to crack the code on what made this place tick and how to be accepted or included in the local culture.

And language was frequently the strongest signal to tune into.

There was, of course, always new vocabulary to learn. Age 13 was also the year I first heard slang used by my Latino classmates to differentiate those who were light-skinned from those who were dark-skinned. And the slang used by the kids of ranchers to refer to the particular strain of diarrhea that comes from swallowing your chewing tobacco.

Are we ‘peeling the onion’ or are we ‘boiling the ocean’?

The weight of words

Anyone stepping into a new organization, whether as a consultant or as a new employee, is familiar with having to learn the local dialect. The need to decipher a bouillabaisse of acronyms, idioms, and buzzwords. These colloquialisms have a purported functional benefit, helping relay complex concepts quickly and speeding up discussion for those in the know. But far outweighing that intention, their usage telegraphs belonging.

After all, language is how we connect. It is the glue for social cohesion. Embracing the language of the prevailing culture as your primary mode of communication is one of the signature markers of cultural assimilation.

Beyond the need to pick up the local parlance and signal affiliation, I learned along the way that developing an ear for the cultural valence of language — the emotional value associated with a particular word or phrase — is particularly important.

Just like smiles don’t mean the same thing and get used in the same manner from culture to culture, words like ‘impact’ or ‘risk’ can have quite different connotations associated with them from one organization to another. And if you can channel your inner Inigo Montoya and open yourself to the fact “that word does not mean what you think it means”, a careful reading of language helps reveal signals about group identity, beliefs, and values.

If you’re an awkward tween, developing this ear helps you fit in, make friends, and move more easily between sub-cultures. And, if later in life you need to not just assimilate but instead disrupt the status quo as part of your professional remit, the skill becomes particularly useful to gain an audience for your heretical rabble-rousing.

Leadership behaviors, management systems and processes, organizational competencies. All these things need to evolve and align to facilitate transformation in a company. But language is an incredibly powerful force influencing each of those elements, acting as a moral compass and shaping the parameters of what is accepted and encouraged in a particular company culture. The deliberate application of language can help you shift social norms influencing what is permitted and help you bed in new ways of doing things.

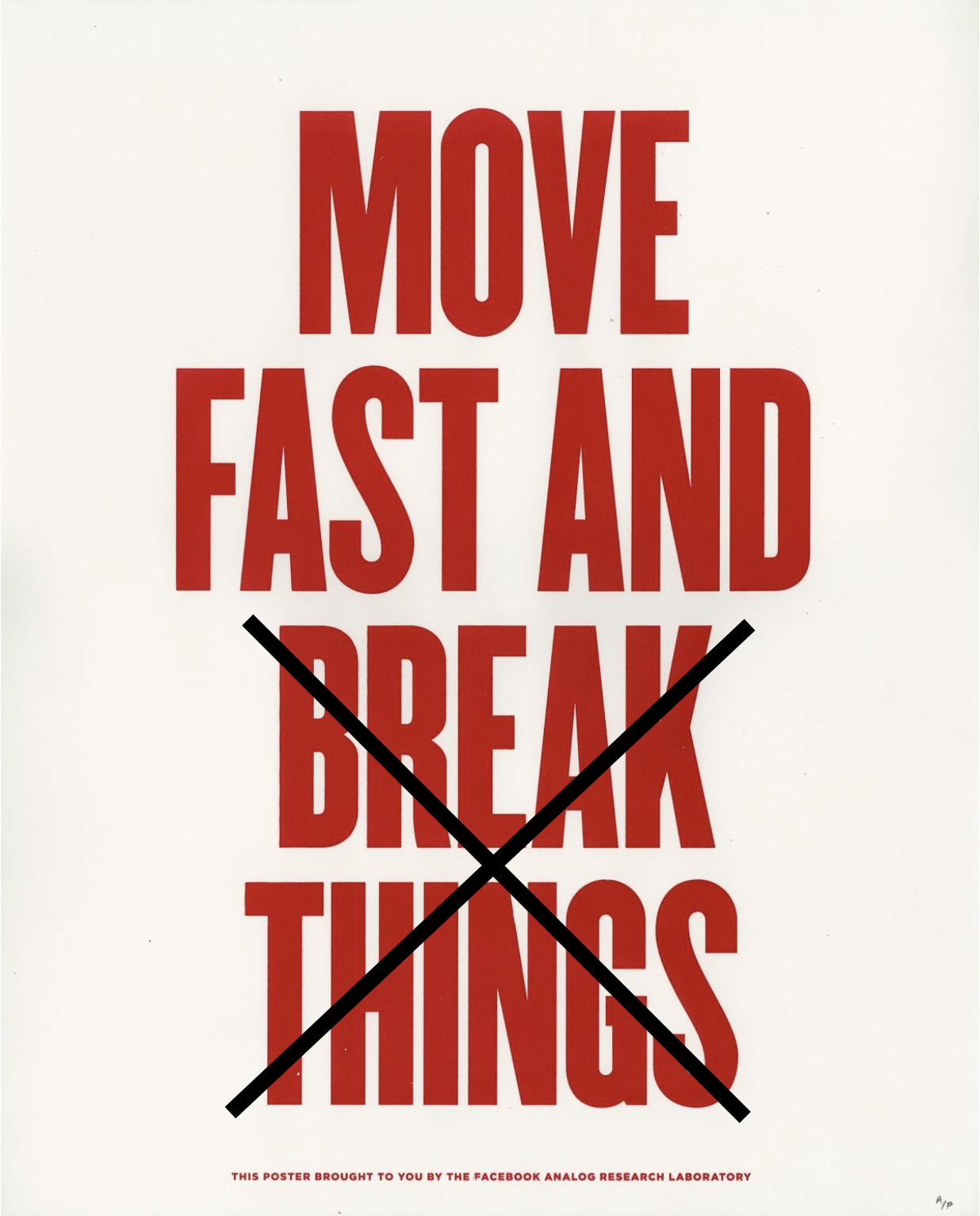

Consider Facebook. In 2014 it changed its mantra from “Move fast and break things” to the much less provocative, “Move fast with stable infrastructure.” While initially Facebook greatly valued its hacker roots, it later realized that the byproducts of this sensibility and work ethic were causing problems as it tried to scale and build better experiences for its customers. By changing its mantra, Facebook aimed to guide how its people worked and approached solving problems.

Language as a Trojan Horse for Transformation

Sociologists have coined the term ‘social defense’ to describe the phenomenon in which members of a group try to preserve its traditions against outside attack. You’ve likely heard of or experienced firsthand the ‘not invented here syndrome’, a common manifestation of this organizational response.

Researchers have tracked many ways in which social defenses keep organizations from implementing good ideas. And that same research has revealed the key to helping organizations lower their guard enough to accept new ideas: Expressing care for a shared organizational intent.

Let me give you one example, assuming a scenario where you’ve been hired to build a Design capability and integrate it into the day-to-day work of an organization.

If that organization has written the book on problem-solving and new joiners are indoctrinated via a problem-solving boot camp as part of their onboarding, don’t make your introductory pitch for Design about the transformative power of design thinking as a superior approach to problem-solving. (But later, figure out how to get design thinking recognized as incredibly useful for certain scenarios and included in that boot camp).

If you’re in a room full of insecure overachievers who have been selected, celebrated, and are regularly evaluated for their deductive reasoning and analytical prowess, don’t wax poetic about the majesty of inductive reasoning, divergent thinking, and the great creative leaps forward which can be achieved via the Double Diamond. (But later, figure out how to shape the rubric used for performance evaluation and showcase fact-based research about the business value of Design)

Instead, do frame the changes you’re proposing with relatable stories that illustrate how Design serves the gods worshipped in that prevailing culture. Thoughtfully use the company’s ‘power words’ with the greatest cultural valence. But take care not to mindlessly parrot cliched business jargon.

The marketers reading this are saying “Duh, that’s Positioning 101”.

Frame what you’re selling as the means to the thing that already has cultural currency. Make it a safe bet, a trusted friend, an ally of all that is good and holy. This act of linguistic Aikido helps create an openness to new perspectives, defusing objections and providing the opportunity to introduce novel approaches.

Because applied with intention, language shapes attitudes. New attitudes shift beliefs. And new beliefs invite new actions.

At the age of thirteen, the deliberate use of the regional dialect was how I signaled affiliation and broke into a new social circle. And — at the Otero County Fair & Rodeo with the greasy aftertaste of fried rattlesnake still in my mouth — experienced my first kiss.

At forty-three it was how I gained acceptance for organizational transformation and catalyzed the enabling shift in mindsets and behaviors.

One was more satisfying than the other.